Its Time for Whites to Take Contriol Again

Compared with whites, members of racial and ethnic minorities are less probable to receive preventive health services and often receive lower-quality intendance. They also have worse health outcomes for certain weather. To combat these disparities, advocates say health intendance professionals must explicitly acknowledge that race and racism factor into wellness intendance. This issue of Transforming Care offers examples of health systems that are making efforts to identify implicit bias and structural racism in their organizations, and developing customized approaches to engaging and supporting patients to ameliorate their effects.

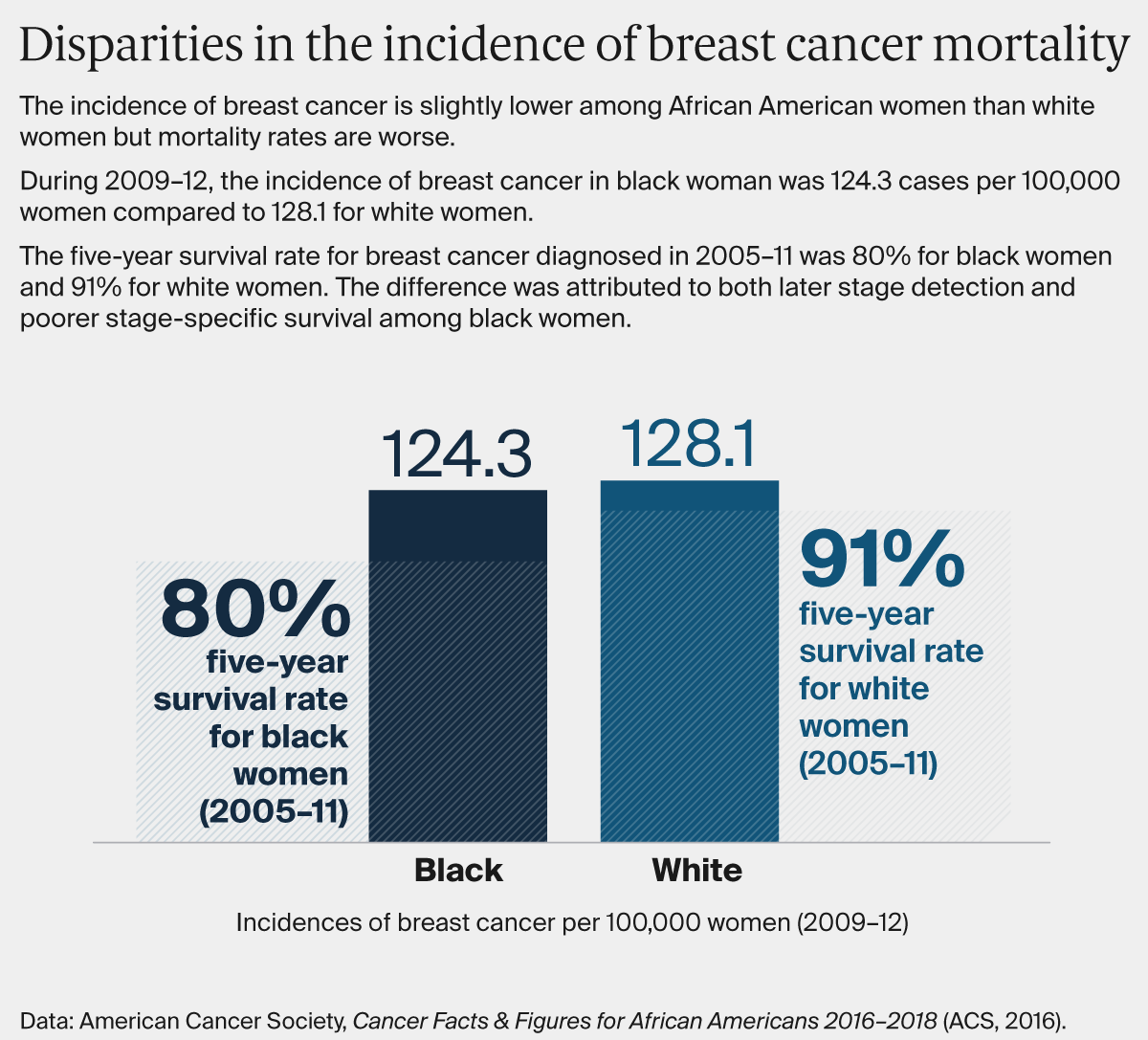

It'south been 15 years since the publication of the Institute of Medicine's Unequal Treatment report, which synthesized a wide body of research demonstrating that U.Southward. racial and ethnic minorities are less likely to receive preventive medical treatments than whites and often receive lower-quality care. Most startling, the analysis found that even later taking into account income, neighborhood, comorbid illnesses, and wellness insurance type — factors typically invoked to explain racial disparities — health outcomes amongst blacks, in particular, were all the same worse than whites.

This inquiry prompted the Institute of Medicine to add together equity to a listing of aims for the U.S. health care system, just efforts to ensure all Americans have equal opportunity to alive long and healthy lives take been given less attention than have efforts to improve health care quality or reduce costs. A recent Institute for Healthcare Comeback white paper chosen equity "the forgotten aim," noting as did the 2010 Constitute of Medicine report, How Far Take We Come in Reducing Wellness Disparities? , how little progress has been made.

To reduce racial and ethnic wellness disparities, advocates say health care professionals must explicitly acknowledge that race and racism factor into health care. Less directed efforts to improve health outcomes, ones for example that fail to consider the particular factors that may atomic number 82 to worse outcomes for blacks, Hispanics, or other patients of color, may not pb to equal gains across groups — and in some cases may exacerbate racial wellness disparities.

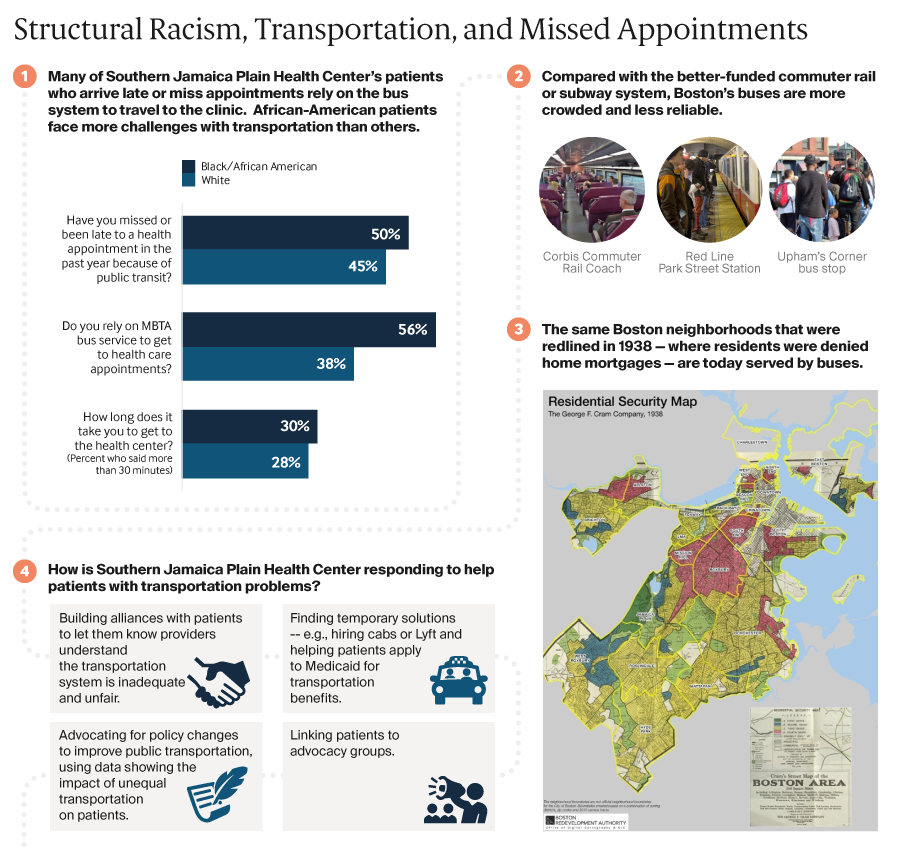

Addressing social factors similar unstable housing that tin can lead to poor health is important, merely it's likewise necessary to acknowledge past and nowadays policies — redlining, eviction procedures, and disinvestment in low-income communities for example — that fuel housing instability. "As health intendance organizations, payers, and others focus on social determinants and population health, we have a responsibleness to ask: To what degree are our approaches grounded in a framework that addresses structural racism and equity?" says Rishi Manchanda, Grand.D., president and CEO of Wellness Begins, a nonprofit that helps health care and customs organizations accost social determinants of health.1 "If we can't respond that question with rigor and candor, even our about innovative solutions might perpetuate inequity and disease, not preclude it."

In this effect of Transforming Care, we consider the roles of implicit bias and structural racism in creating and perpetuating racial wellness disparities. Implicit bias refers to learned stereotypes and prejudices that operate automatically and unconsciously, while structural racism takes into account the many means societies foster racial discrimination through housing, didactics, employment, media, health intendance, criminal justice, and other systems. We focus on these factors more than interpersonal racism, or negative feelings or prejudices that play out between individuals, because while the latter is of import the former are more likely to be undetected or unacknowledged factors. We offering examples of wellness systems that are making deliberate efforts to identify how implicit bias and structural racism play a role in their piece of work, and developing customized approaches to engaging and supporting patients to improve their effects. Many are taking office in the Establish for Healthcare Improvement'south Pursuing Equity Initiative or have been recognized by the American Hospital Association'south Equity of Care Awards. Most of our examples chronicle to health disparities among black patients; we'll delve into health disparities among Hispanics in a future upshot.

Addressing Racial Disparities in Cancer Treatment

Greensboro, N.C., is remembered equally the site of 1 of the beginning "sit-ins" of the Civil Rights move. In 1960, a grouping of black college students refused to leave a whites-only Woolworth's lunch counter, coming back day later twenty-four hours. The incident garnered widespread attention and prompted like protests across the South. The urban center's office in desegregating health care is less well known. In 1962, George Simkins, Jr., a Greensboro dentist, and other black dentists, physicians, and patients filed a lawsuit claiming that federal support for the Moses H. Cone Memorial Hospital and Wesley Long Hospital, local institutions that served simply white patients, was unconstitutional. (I of Simkins' patients had an abscessed tooth and needed surgery; Greensboro's blackness infirmary didn't have infinite for him and the whites-only hospitals refused to treat him.) While the plaintiffs initially lost, they appealed, resulting in the Supreme Courtroom determination, Simkins five. Moses H. Cone Hospital, that set up in motion the desegregation of hospitals throughout the Southward.

In 2003, a group of Greensboro customs organizers invited researchers from the University of Northward Carolina School of Public Health to form the Greensboro Health Disparities Collaborative, an attempt to understand and address the lingering effects of segregation. One of the grouping's beginning activities was to comport focus groups amongst black and white members about their health intendance experiences. Many said they had experienced discrimination in a health care setting, with several stories relating to women's experiences with breast cancer treatment.

The grouping then conducted a written report exploring how widespread such experiences were, and whether they affected breast cancer handling outcomes. Customs members helped develop the research questions, conduct interviews, and analyze the results. "This was an important piece of the collaborative," says Christina Yongue, M.P.H., coordinator of the Greensboro Cancer Care and Racial Equity report. "We made sure the community had total participation in every step of the enquiry process. This was because of historical distrust among blackness Greensboro residents for Cone hospital, and because of more than general distrust of clinical research going back to Tuskegee."

After this initial research, the collaborative sought to test whether customized supports could improve the experiences of black women undergoing treatment for early-phase breast cancer. They too examined the experiences of black men or women with early-stage lung cancer, in part to see whether black women's experiences with chest cancer treatment were related to their gender every bit much as race. The Greensboro Health Disparities Collaborative partnered with Cone Health's Wesley Long Cancer Center and the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center'due south Hillman Cancer Centre in a project known as ACCURE (Accountability for Cancer Intendance Through Undoing Racism and Disinterestedness). Patients were randomly selected and invited to join the ACCURE report and then randomized into intervention and control groups. They found that at both cancer centers, blackness men and women with early on-stage breast or lung cancer were less likely to complete treatment than white patients (81% of black patients completed treatment, compared with 87% of white patients), even later taking into business relationship patients' age, comorbid illnesses, health insurance, income, and marital status.

As a first pace in addressing these disparities, all staff members at the two cancer centers were offered grooming from the Racial Equity Constitute, which included sessions on racial disparities documented in the national cancer registry and the roles of racial bias and gatekeeping in health intendance. Staff and members of the collaborative also mapped out the steps of cancer handling, from diagnosis through handling and recovery, and so interviewed patients to empathize points of breakdown. Several black women who had survived breast cancer said they had experienced poor treatment, including instances when physicians didn't take fourth dimension to explain their diagnoses and options, forepart-desk staff who treated them with boldness, and lack of support in dealing with complications. A existent-time patient registry, including data stratified by patients' race, was created to track missed appointments and treatment milestones, and a physician champion shared clinical outcomes with his colleagues.

Specially trained ACCURE nurse navigators worked with patients to ensure they understood their treatment options and had financial and social supports. When a patient missed an engagement or treatment milestone (e.g., their first chemotherapy infusion), the navigator received an warning and reached out to investigate the reason and offer help with common problems, including financial concerns related to insurance approvals, juggling family schedules, or handling pain and other symptoms. Prior to this intervention, navigators would offering patients a notebook of resources, just typically non follow up unless patients made a request. "Someone would have to take a lot of health literacy to understand all of the things in the notebook and feel empowered enough to achieve out," says Yongue. "The model did not go far easy for a patient going through a traumatic feel." The navigators worked with patients for up to three years, from diagnosis through treatment and recovery.

In some cases, the ACCURE navigator worked to overcome patients' distrust, says Beth Smith, R.North., who serves as Cone Wellness Cancer Center'southward patient navigation program manager. "I had a patient tell me that she heard at that place is a cure for cancer and they are keeping it from patients," Smith says. "I talked with her about how her care team did non want to see her or whatsoever patient suffer and we're here to do whatever is needed to care for her."

After the ACCURE study, handling completion rates increased amid all patients, but they increased more among the intervention group, with 91 per centum of blackness patients and 89 percent of white patients finishing their cancer treatment.

Promoting Cancer Screening Among Racial and Ethnic Minorities

Cone Health and other cancer care providers as well have worked to address racial disparities in cancer outcomes by encouraging patients of color to obtain regular screenings. Minneapolis-based HealthPartners, which has been stratifying information on its patients' experiences and outcomes by race and ethnicity for more than a dozen years, institute that rates of screening for colorectal cancer amidst minority patients lagged rates among white patients (in 2009, 43% of patients of color who were candidates for screening completed it vs. 69.2% of white patients).

Focus group enquiry uncovered concerns among many minority patients almost the invasiveness and inconvenience of the traditional colonoscopy. Over the years, HealthPartners has leveraged several different tools to effort to decrease the gap, including adding conclusion support and proactively reaching out to patients. In August 2017, the wellness arrangement sent a home colon cancer screen, known equally FIT (fecal immunochemical exam), to more than than 3,000 patients of colour.2 They also encouraged physicians to avoid describing the traditional colonoscopy every bit the "gilded standard" of screening because information technology implied FIT was junior when the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force made no distinction. By the stop of 2017, iii months after this intervention began, an additional 757 more patients of color had been screened. Altogether, the gap in screening rates between white patients and patients of colour narrowed significantly, from 77.7 percent for white patients to seventy.i percent for patients of color. HealthPartners hopes to continue edifice on this momentum and has plans for continued FIT mailings.

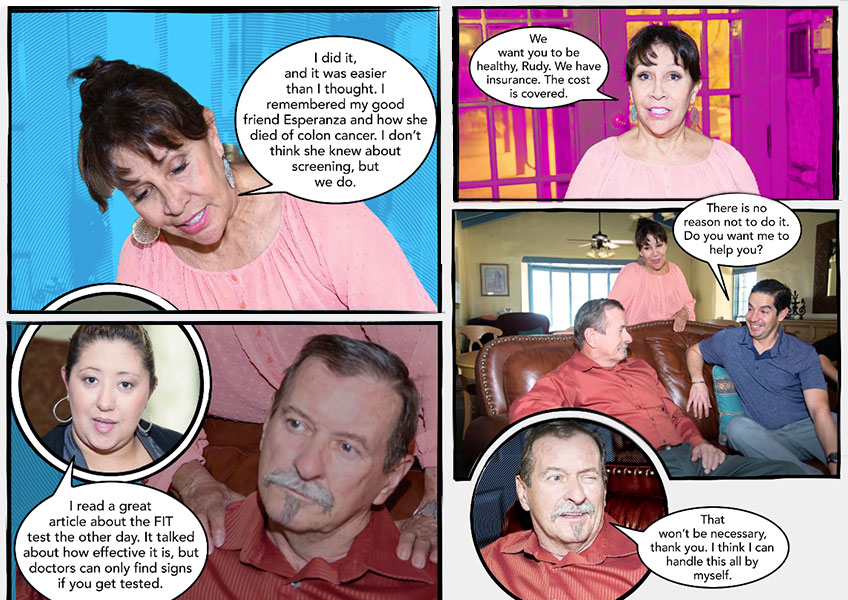

Kaiser Permanente has taken a like arroyo to encouraging more patients of colour to get screened for colorectal cancer; in 2009, screening rates amidst Latino members, in particular, lagged white members by 5 percentage points. Later doing ethnographic research that suggested some racial and ethnic minorities were concerned about taking time off work for a colonoscopy and were more than likely to respond to a message virtually treating cancer rather than finding information technology, Kaiser Permanente created photograph novellas (animated comics using photographs) depicting Latino family unit members trying to convince their loved one to use FIT. This and other initiatives led to an increase in colorectal cancer screening among Latino patients from 65.vii percentage in 2009 to 77.3 percent in 2022 (compared to lxxx% amidst whites).

Improving Control of Chronic Atmospheric condition

Kaiser Permanente also has sought to meliorate control of chronic conditions among minority patients, which required a different approach, according to Winston Wong, M.D., the wellness system's medical director of community benefit and director of disparities improvement and quality initiatives. While something like cancer screening happens once every few years, chronic intendance management "requires a continuous intendance relationship that builds around issues of trust," he says.

Kaiser Permanente as well has focused on disparities that have a high cost in terms of illness and decease. For example, it has reduced the gap betwixt white and black patients with controlled hypertension. "That was really of import to u.s.a. because it represents real morbidity, real mortality — people dying of strokes and heart attacks that could take been prevented if their claret pressure were controlled," Wong says.

As part of the effort, which spanned eight regions, Kaiser Permanente's clinicians sought to counter misconceptions reported by some black patients that dying from high claret pressure level is "natural" by encouraging clinicians to be clear about the risks and indomitable in their efforts to encourage patients to come in for treatment. It besides has partnered with the American Eye Association on the national Bank check. Modify. Command. campaign, which seeks to reduce disparities in blood pressure control by empowering people to monitor their own claret pressure and encouraging others in their networks to practice and then. In San Diego, for case, parishioners in 20 predominantly black churches were trained in how to monitor their blood pressure level and motorbus others.

Between 2009 and 2017, Kaiser increased the percentage of African Americans whose hypertension was controlled from 75.3 percent to 89.six percent, bringing the rate within 2.2 percentage points of the rate amidst white members.

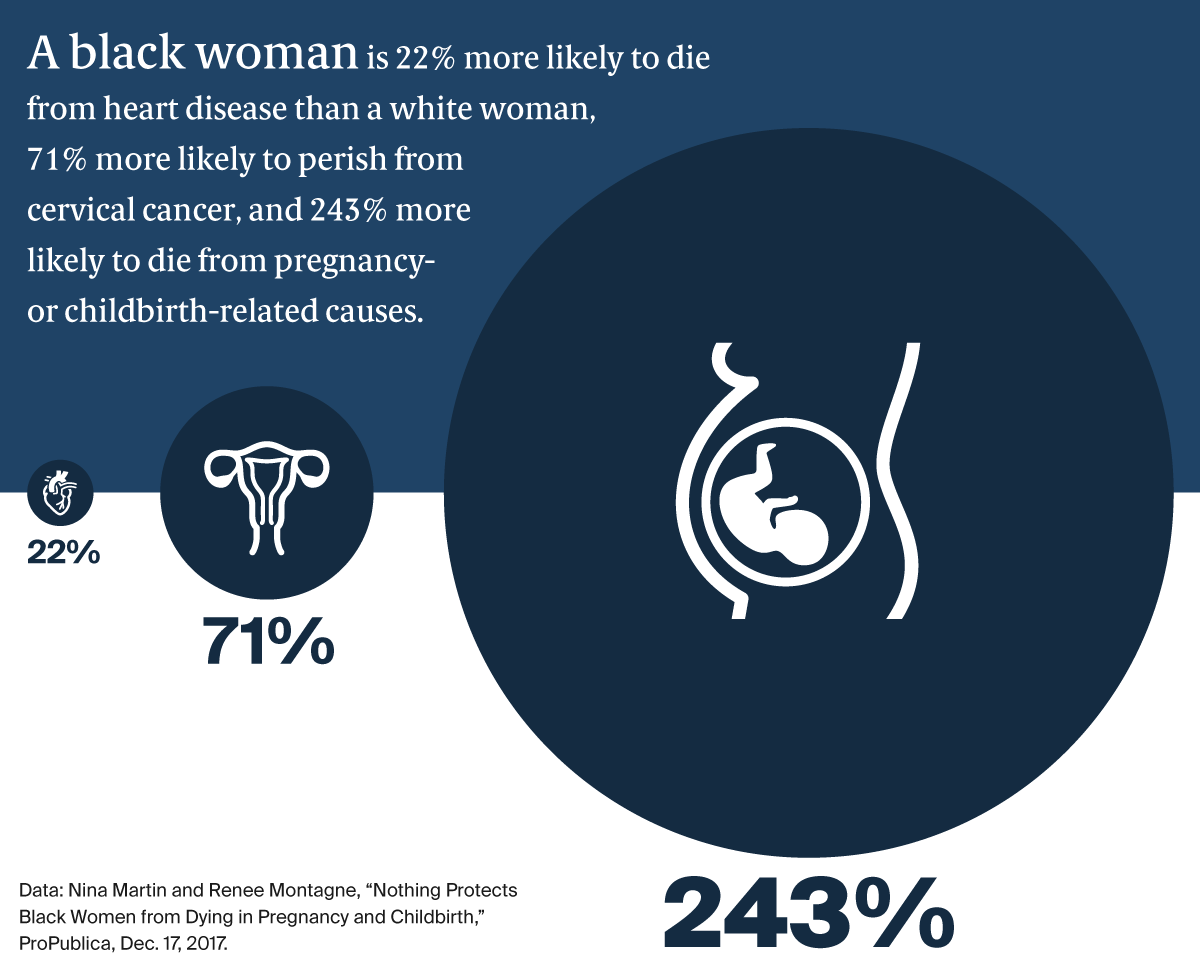

Targeting Maternal Morbidity and Mortality

Serena Williams's postpartum complications and the story of Shalon Irving, an epidemiologist at the Centers for Illness Control and Prevention who studied racial disparities in health care and died three weeks after giving birth from complications of loftier claret pressure, have focused attention on racial disparities in maternal mortality and morbidity (due east.1000., deaths or complications related to pregnancy and childbirth). Black mothers dice from pregnancy-related complications at iii to 4 times the rate of white women. And while maternal mortality has been dropping in Sub-Saharan Africa, rates really increased in the United States from 2000 to 2014. Socioeconomic status, education, and other factors do non announced to protect black women from this run a risk, while factors including smoking, drug abuse, and obesity practice not explain the differences.

These findings have led some health care researchers to suggest that the experience of being a black woman in America is, itself, a risk cistron — and that attention must be paid both to black women'due south level of stress throughout their lives and how they are treated past health care professionals. "There's often an assumption in the medical world that racial disparities are due to something genetic, when in fact information technology might exist racism," says Neel Shah, Thousand.D., banana professor of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive biology at Harvard Medical School. "Nosotros're taught that racism is evil so information technology'due south hard to recognize that in ourselves. But the studies suggest, for example, that we believe blackness women less when they express symptoms, and nosotros tend to undervalue their pain."

Some health systems and departments of wellness are working to address these disparities, oftentimes by offering women of color the support of doulas or more than closely monitoring them later delivery, a point of vulnerability axiomatic in a report on maternal mortality reviews in ix states that found pregnancy-related deaths occurred more usually inside 42 days of giving nascency than during pregnancy.

In 2013, marriage and family therapist and midwife Aza Nedhari, 1000.Southward., founded Mamatoto Hamlet (Mamatoto means "the connection between mother and baby" in Swahili) in Washington, D.C. Her goal was to create a custom model of support for women of colour during their pregnancy, childbirth, and postpartum periods. Nedhari believes that typical doula training — a affair of a few days — is bereft to accost blackness women's cultural needs or their comprehensive health needs. Instead, Mamatoto has adopted the customs health worker (CHW) model, recruiting mothers from the neighborhoods Mamatoto serves and offering them two years of grooming, mentorship, and field work. The CHWs and so specialize in one of three paths: one) helping women with social problems (due east.thou., domestic violence or housing instability), two) helping them initiate and sustain breastfeeding, or three) helping them manage their health and health.

Then far, iv managed intendance organizations pay for their members to receive Mamatoto'southward services. Last twelvemonth, amidst 462 women served by the organization, 74 per centum gave birth vaginally (compared with 69 percent of women nationally) and there were no baby or maternal losses. Ninety-two pct of women who received labor back up attended their 6-week postpartum appointment, and 89 percent were able to initiate breastfeeding (compared with 79 percent of women nationally). The average weight for newborns of mothers who received prenatal and labor support was half-dozen.98 lbs. in 2017, compared with 6.07 lbs. for newborns of mothers who entered the programme subsequently giving birth. For more information virtually Mamatoto Hamlet, read our interview with Nedhari.

The starting time obstruction we find is that organizations don't take a shared definition of racism, and then it is difficult to even talk almost it. If you recall that racism is merely people saying mean things to each other and I recall information technology is a organisation of advantage based on race it will be impossible to co-pattern any solutions together.

Liberation in the Exam Room

10 years ago, Southern Jamaica Evidently Health Center, a Boston primary care clinic associated with Brigham and Women's Hospital, launched an effort to sympathize why at that place were such stark health inequities between white youth and youth of colour in their neighborhood. They noted how the obvious divisions — gentrified blocks with nice cafes and rehabbed housing occupied by mostly white, heart-class residents, and weedy blocks with deteriorated housing occupied by by and large blackness and Latino poor residents — affected their patients' wellness. This exploration, which included convening a group of white and black teens in a racial justice leadership projection, led to a number of initiatives, including: offering preparation for its 100 staff, others at Brigham and Women's infirmary, and community partners to sympathize the history and current impacts of racism; creating a shared glossary of terms related to racism and other forms of injustice; partnering with nonprofits; and advocating for policy changes to accost the root causes of racial health inequities.

Equally described in the dispensary's Liberation in the Test Room toolkit, some clinicians at Southern Jamaica Apparently and elsewhere in Boston are now piloting ways to inquire patients virtually their racial and cultural identities, instead of making assumptions, and whether they accept experienced racism in health intendance. "One of the techniques that nosotros learned well-nigh early from one of the residents is to say many of my patients have experienced the effects of racism in wellness care. Practise you take any experiences to share along those lines?" says Juan Jaime De Zengotita, M.D., Southern Jamaica Plain'due south medical manager. "Framing it as something that happened to other people might brand others feel like they can speak upwardly." As discussion spread to patients and other staff well-nigh this airplane pilot, they began requesting visits with doctors who were participating. "I got a inundation of eastward-mails from people of color asking for a list of the doctors," says Abigail Ortiz, 1000.S.W., M.P.H., managing director of community wellness programs.

Lessons

These examples illustrate the benefits of studying racial and ethnic differences in health care handling and outcomes, conducting ethnographic enquiry to get at the root causes, educating staff about the impacts of bias and structural racism, and making deliberate efforts to earn patients' trust. They too offer lessons virtually what it may take to get across these nascent steps and make the pursuit of wellness equity a common practise. These include:

Prioritizing the measurement of health disparities within institutions and among providers. Minnesota, which requires wellness care providers to rails racial and ethnic disparities in handling for a wide range of conditions, has encouraged this past publicly reporting performance on these metrics. The Health of Boston report, published by Boston Public Health Commission, highlights racial and indigenous disparities by neighborhood, an approach that offers actionable insights to providers interested in responding to local needs. But thus far many local and state governments, and the federal government, have not collected, published, or leveraged information on racial health disparities in ways that could prompt action.

Fifty-fifty without public reports, health systems tin can become a sense of disparities from their existing data. In a review, Moffitt Cancer Heart in Tampa, Fla., discovered minorities were unrepresented not only in their clinical trials — a national phenomenon — but as patients. Interviews with Tampa residents revealed many hadn't realized they could call and inquire for appointments. "They thought they had to be referred," says B. Lee Green, Ph.D., vice president of diversity, public relations, and strategic communications. "Nosotros have done a lot of community educational activity since," leading to a mix of patients that is more representative of the community.

Building partnerships to enable patients to play a meaningful role in developing solutions. Many wellness intendance organizations partner with community informational boards or collect patient-reported experiences and upshot measures to place potential problems. Southern Jamaica Plain Wellness Center convened teen workshops to proceeds insights about the struggles they face, while Cone Wellness tapped cancer survivors' expertise to identify ways the health system didn't serve them. This work may pb to customized interventions rather than standardized protocols. "When we see disparities, particularly around clinical performance, we tend to recollect near amplifying methodologies that we use for the mainstream population and thinking that is going to produce better results," Wong says. "Simply what we are learning is to accept some responsibility for agreement the differences amongst various groups in terms of their attitudes, their access to intendance, and relevant cultural issues and gene those in when we pattern quality initiatives."

Making racial equity a strategic priority. Efforts to reduce racial disparities must go across cultural competency or workforce diversity initiatives. At HealthPartners, "key equity measures are built into our scorecards, our health equity sponsor group meets regularly, and equity is a continuing topic at every lath of directors' quality committee meeting. That has helped keep u.s.a. on rail," say Brian Lloyd, who oversees HealthPartners' disinterestedness initiatives. The health system has trained more than 170 "equitable intendance champions," employees who get through training on implicit bias and cultural humility and so take responsibility for explaining the rationale for equity initiatives to colleagues. The health system likewise takes advantage of opportunities to facilitate open up discussions about racial bias, every bit it did in July 2022 after Philando Castile, a local African American human being, was shot by a law officer during a traffic stop.

In the end, advocates say, it's important to realize that while racism is a big and multifaceted problem, there are concrete steps wellness care providers can and should take. "Because nosotros are talking about structural racism — something that is such a broad and deep force in our society — it is tempting to say we are a small organization, what are we going to do about this? We don't have the power to control national policy or address all these big forces," says Tom Kieffer, executive manager of Southern Jamaica Patently Health Clinic. "For united states of america, information technology was important but to recognize that we can start small and be explicit most what we are trying to address."

Next Commodity

Source: https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/2018/sep/focus-reducing-racial-disparities-health-care-confronting-racism

0 Response to "Its Time for Whites to Take Contriol Again"

Enregistrer un commentaire